Etruscan language

| Etruscan | ||

|---|---|---|

| mechl Rasnal | ||

| Spoken in | ||

| Region | Italian Peninsula | |

| Language extinction | 1st century AD | |

| Language family | Tyrrhenian | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | None | |

| ISO 639-2 | und | |

| ISO 639-3 | ett | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

The Etruscan language was spoken and written by the Etruscan civilization in what is now present-day Italy, in the ancient region of Etruria (modern Tuscany plus western Umbria and northern Latium) and in parts of Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna (where the Etruscans were displaced by Gauls). Latin, however, superseded Etruscan completely, leaving only a few documents and a few loanwords in Latin e.g., persona from Etruscan φersu, and some place-names, such as Roma.

Contents |

History of Etruscan literacy

Etruscan literacy was widespread over the Mediterranean shores, as can be seen by about 13,000 inscriptions (dedications, epitaphs etc.), most fairly short, but some of some length.[1] They date from about 700 BC.[2]

The Etruscans had a rich literature, as noted by Latin authors. Unfortunately only one book (now unreadable) has survived. By AD 100, Etruscan had been replaced by Latin.

Only a few educated Romans with antiquarian interests, such as Varro, could read Etruscan. The last person known to have been able to read it was the Roman emperor Claudius (10 BC – AD 54), who — in the context of his work in twenty books about the Etruscans, Tyrrenikà (now lost) — compiled a dictionary (also lost) by interviewing the last few elderly rustics who still spoke the language. Urgulanilla, his first wife, was Etruscan.[3]

Livy and Cicero were both aware that highly specialized Etruscan religious rites were codified in several sets of books written in Etruscan under the generic Latin title Etrusca Disciplina. The Libri Haruspicini dealt with divination from the entrails of the sacrificed animal, the Libri Fulgurales expounded the art of divination by observing lightning. A third set, the Libri Rituales, would have provided us with the key to Etruscan civilization: its wider scope embraced Etruscan standards of social and political life as well as ritual practices. According to the 4th century Latin writer Servius, a fourth set of Etruscan books existed, dealing with animal gods, but it is probably unlikely that any contemporary scholar could have read Etruscan at such a late date. The single surviving Etruscan book, Liber Linteus, being written on linen, survived only by being used as mummy wrappings.

Etruscan had some influence over Latin. A few dozen words were borrowed by the Romans and some of them can be found in modern languages.

Geographic distribution

Inscriptions have been found in north-west and west-central Italy, in the region that even now bears the name of the Etruscans, Tuscany (from Latin tuscī "Etruscans"), as well as in today's Latium north of Rome, in today's Umbria west of the Tiber, around Capua in Campania and in the Po valley to the north of Etruria. Presumably this range is a maximum Italian homeland where the language was at one time spoken.

Outside of Italy[4] inscriptions have been found in Africa, Corsica, Elba, Gallia Narbonensis, Greece, the Balkans and the Black Sea. By far the greatest concentration is in Italy.

An inscription found on Lemnos in 1886, is in an alphabet practically identical to that of Etruscan.

Classification

The Etruscan language has been difficult to analyze, which is attributable to its being an isolate. The phonology is known through the alternation of Greek and Etruscan letters in some inscriptions (for example, the Iguvine Tables), and many individual words are known through loans into or from Greek and Latin, as well as explanations of Etruscan words by ancient authors. A few concepts of word formation have been formulated (see below). Knowledge of the language is incomplete.

The ancients were aware that Etruscan was an isolate. In the 1st century BC the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus stated that the Etruscan language was unlike any other.[5] Bonfante, a leading scholar in the field, says "... it resembles no other language in Europe or elsewhere ...."[1]

Tyrsenian family

The majority consensus is that Etruscan is related only to other members of what is called the Tyrsenian language family which in itself is an isolate family, that is, unrelated to other language groups by any known relationship. Since Rix (1998) it is widely accepted that Tyrsenian is composed of Rhaetic and Lemnian together with Etruscan.

Another possible Aegean language related with Etruscan is Minoan. The idea of a relation between the language of the Aegean Linear scripts was taken into consideration as the main hypothesis by Michael Ventris before discovering that in fact the language behind the more modern Linear B script was Mycenean, a Greek dialect. Facchetti, a researcher who has dealt with both languages (Etruscan and Minoan) has put forward again this hypothesis, comparing some of the Minoan words of known meaning with some similar Etruscan words [6]

Some modern scholars[7] assert that the Tyrsenian languages are distantly related to the Indo-European family. More specifically Frederik Woudhuizen suggests a relation to the Anatolian branch of the family. Woudhuizen revived a conjecture to the effect that the Tyrsenians came from Anatolia, including Lydia, whence they were driven out by the Cimmerians in the early Iron Age, 750-675 BC, leaving some colonists on Lemnos. He makes a number of comparisons of Etruscan to Luwian and asserts that Etruscan is modified Luwian. He accounts for the non-Luwian features as a Mysian influence: "deviations from Luwian ... may plausibly be ascribed to the dialect of the indigenous population of Mysia."[8] According to Woudhuizen, the Etruscans were colonizing the Latins. The Etruscans brought the alphabet from Anatolia.

More recently Robert S.P. Beekes presented a similar case, but argued that the people later known as the Lydians and Etruscans had originally lived in north west Anatolia, with a coastline to the Sea of Marmara, whence they were driven by the Phrygians c. 1,200 BC, leaving a remnant known in antiquity as the Tyrsenoi. A segment of this people moved south-west to Lydia, becoming known as the Lydians, while others sailed away to take refuge in Italy, where they became known as Etruscans. The Etruscan language could therefore have been related to a non-Indo-European substratum of Lydian.[9]

Both of these accounts draw on the story by Herodotus (i, 94) of the Lydian origin of the Etruscans. Dionysius of Halicarnassus (book 1) rejected this account of the people he called the Tyrrhenians, partly on the authority of Xanthus, a Lydian historian, who had no knowledge of the story, and partly on what he judged to be the different languages, laws and religions of the two peoples.

Another proposal, currently pursued mainly by a few linguists from the former Soviet Union, suggests a relationship with Northeast Caucasian (or Nakh-Daghestanian) languages.[10] [11]

Other

Historically, a relation of Etruscan to the Semitic languages has also been discussed. This suggestion has been obsolete since the later 19th century. Various other speculative proposals have been made in the 19th and 20th centuries, all of them failing to gain significant acceptance.

The interest in Etruscan antiquities and the mysterious Etruscan language found its modern origin in a book by a Dominican friar, Annio da Viterbo (d. 1502), also known as Il Pastura, the cabalist and orientalist, now remembered mainly for literary forgeries. He guided Pinturicchio's allegorical frescoes for Pope Alexander VI's Vatican apartments. In 1498 Annio published his antiquarian miscellany titled Antiquitatum variarum (in 17 volumes) where he put together a fantastic theory in which both the Hebrew and Etruscan languages were said to originate from a single source, the "Aramaic" spoken by Noah and his descendants, founders of Etruscan Viterbo. Annio also started to excavate Etruscan tombs, unearthing sarcophagi and inscriptions, and made a bold attempt at deciphering the Etruscan language. The theory of the Semitic origins still found its supporters in 19th century scholarship. In 1858, the last attempt was made by Johann Gustav Stickel, Jena University: "Das Etruskische (...) als Semitische Sprache erwiesen". A reviewer concluded that Stickel brought forward every possible argument which would speak for that hypothesis, but he proved the opposite of what he had attempted to do (Johannes Gildemeister in ZDMG 13, 1859, 289-304).

A Ural-Altaic connection with the Etruscan Language has also been proposed. The French orientalist Baron Carr[12]a de Vaux had shown the connections between Etruscan and Altaic Languages. In 1874, the British priest Isaac Taylor[13] brought up the idea of a genetic relationship between Etruscan and Hungarian.

In 1861 Robert Ellis proposed that Etruscan was related to Armenian.[14] Some scholars also see in Urartian art, architecture, language and general culture traces of kinship to the Etruscans of the Italian peninsula.[15]

Relation with Albanian in particular has been advanced by a number of people, notably Zacharie Mayani, as well as earlier writers such as Ascoli, 1877, E. Schneider, 1889, Thomopoulos, 1912, Buonamici, 1919.[16]

Writing system

Alphabet

The Latin alphabet owes its existence to the Etruscan writing system, which was adapted for Latin in the form of the Old Italic alphabet. The Etruscan alphabet[17] employs a Euboean variant[18] of the Greek alphabet using the letter digamma and was in all probability transmitted through Pithecusae and Cumae, two Euboean settlements in southern Italy. This system is ultimately derived from West Semitic scripts.

The Etruscans recognized a full 26-letter alphabet, which they depicted as itself for decoration on some objects such as an occasional ink-jar; for example, the "rooster ink-stand."[19] This has been termed the model alphabet.[20] They did not use four letters of it, mainly because Etruscan had no voiced stops, b, d and g, and also no o. They innovated one letter for f.[18]

Text

Writing was from right to left except in archaic inscriptions, which might use boustrophedon. An example found at Cerveteri used left to right. In the earliest inscriptions, the words are continuous. From the 6th century BC, they are separated by a dot or a colon, which might also separate syllables. Writing was phonetic; the letters represented the sounds and not conventional spellings. On the other hand, many inscriptions are highly abbreviated and often casually formed, so the identification of many individual letters is sometimes difficult. Spelling might vary from city to city, probably reflecting differences of pronunciation.[21]

Impossible consonant clusters

Speech featured a heavy stress on the first syllable of a word, causing syncopation by weakening of the remaining vowels, which then were not represented in writing: Alcsntre for Alexandros, Rasna for Rasena.[18] This speech habit is one explanation of the Etruscan "impossible consonant clusters." The resonants however may have been syllabic, accounting for some of the clusters (see below under Consonants). In other cases the scribe sometimes inserted a vowel: Greek Herakles became Hercle by syncopation and then was expanded to Herecele. Pallottino[22] regarded this variation in vowels as "instability in the quality of vowels" and accounted for the second phase (e.g. Herecele) as "vowel harmony, i.e., of the assimilation of vowels in neighboring syllables ...."

Phases

The writing system had two historical phases: the archaic, 7th to 5th century BC, which used the early Greek alphabet, and the later, 4th to 1st century BC, which modified some of the letters. In the later period syncopation increased.

The alphabet went on in modified form after the language disappeared. In addition to being the source of the Roman alphabet, it has been suggested that it passed northward into Venetic and from there through Raetia into the Germanic lands, where it became the Futhark, a system of runes.[23]

Media

Bilingual texts

The Pyrgi Tablets are a bilingual text in Etruscan and Phoenician engraved on three gold leaves, one for the Phoenician and two for the Etruscan. The Etruscan is in 16 lines, 37 words. The date is roughly 500 BC.[24]

The tablets were found in 1964 by Massimo Pallottino during an excavation 20 miles from the city of Rome, at the ancient Etruscan port of Pyrgi.

Longer texts

According to Rix and his collaborators only two unified (though fragmentary) texts are available in Etruscan:

- The Liber Linteus used for mummy wrappings (at Zagreb, Croatia). Roughly 1200 words of readable text, mainly repetitious prayers yielding about 50 lexical items.[24]

- The Tabula Capuana (the inscribed tile from Capua). About 300 readable words in 62 lines, dating to the 5th century BC.

Some additional longer texts are:

- The lead foils of Punta della Vipera,[25] about 40 legible words having to do with ritual formulae. Dated to about 500 BC.

- The Cippus Perusinus, a stone slab (cippus) found at Perugia. Contains 46 lines, 130 words.

- The Tabula Cortonensis, a bronze tablet from Cortona recording a legal contract. About 200 words.

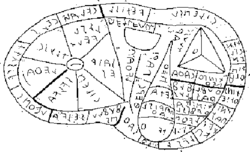

- The Piacenza Liver, a bronze model of a sheep's liver representing the sky, with the engraved names of the gods ruling different sections.

Inscriptions on monuments

The main material repository of Etruscan civilization is or was its tombs. Public and private buildings were dismantled and the stone reused centuries ago. The tombs remain as they were except for the ravages of time and the activities of plunderers. More tombs continue to be found regularly.

The tombs are the main source of portables in collections throughout the world, provenance unknown. The Etruscans lived well and valued art. Their objets d'art are of incalculable value, causing a brisk black market and equally brisk law enforcement effort. It is against the law to remove objects from Etruscan tombs unless authorized by the Italian government.

The total number of tombs is unknown due to the magnitude of the task of cataloguing them. They are of many different types. Especially fruitful are the hypogeal or "underground" chamber or system of chambers cut into tuff and covered by a tumulus. The interior of the tomb represents a habitation of the living stocked with furniture and favorite objects. The walls may display painted murals, the predecessor of wallpaper. Tombs are identified as Etruscan dating form the Villanovan period to about 100 BC, when presumably the cemeteries were abandoned in favor of Roman ones.[26] Some of the major cemeteries are as follows:

- Caere or Cerveteri, a UNESCO site.[27] Three complete necropolises with streets and squares. Many hypogea are concealed beneath tumuli retained by walls; others are cut into cliffs. The Banditaccia necropolis contains more than 1000 tumuli. Access is through a door.[28]

- Tarquinia, Tarquinii or Corneto, a UNESCO site.[27] Approximately 6000 graves dating from the Villanovan (9th & 8th centuries BC) distributed in necropolises, the main one being the Monterozzi hypogea of the 6th - 4th centuries BC. About 200 painted tombs display murals of various scenes with call-outs and descriptions in Etruscan. Elaborately carved sarcophagi of marble, alabaster and nenfro include identificatory and achievemental inscriptions. The Tomb of Orcus at the Scatolini necropolis depicts scenes of the Spurinna family with call-outs.[29]

- Inner walls and doors of tombs and sarcophagi.

- Engraved steles (tombstones)

- ossuaries

Inscriptions on portable objects

Votives

Votive gifts

Specula

A speculum is a circular or oval hand-mirror used predominantly by Etruscan women. Speculum is Latin; the Etruscan word is malena or malstria. Specula were cast in bronze as one piece or with a tang into which a wooden, bone or ivory handle fitted. The reflecting surface was created by polishing the flat side. A higher percentage of tin in the mirror improved its ability to reflect. The other side was convex and featured intaglio or cameo scenes from mythology. The piece was generally ornate.[30]

About 2300 specula are known from collections all over the world. As they were popular plunderables, the provenance of only a minority is known. An estimated time window is 530-100 BC.[31] Most probably came from tombs.

Many bear inscriptions naming the persons depicted in the scenes, for which reason they are often called picture bilinguals. In 1979, Massimo Pallottino, then president of the Istituto di Studi Etruschi ed Italici initiated the Committee of the Corpus Speculorum Etruscanorum (CSE), which resolved to publish all the specula and set editorial standards for doing so.

Since then the committee has grown, acquiring local committees and representatives from most institutions owning Etruscan mirror collections. Each collection is published in its own fascicle by diverse Etruscan scholars.[32]

Cistae

A cista is a bronze container of circular, ovoid or more rarely rectangular shape used by women for the storage of sundries. They are ornate, often with feet and lids to which figurines may be attached. The internal and external surfaces bear carefully crafted scenes usually from mythology, usually intaglio, rarely part intaglio, part cameo.

Cistae date from the Roman Republic of the 4th and 3rd centuries BC in Etruscan contexts. They may bear various short inscriptions concerning the manufacturer or owner or subject matter. The writing may be Latin, Etruscan or both.

Excavations at Praeneste, an Etruscan city turned Roman, turned up about 118 cistae, one of which has been termed "the Praeneste cista" or "the Ficoroni cista" by art analysts, with special reference to the one manufactured by Novios Plutius and given by Dindia Macolnia to her daughter, as the archaic Latin inscription says. All of them are more accurately termed "the Praenestine cistae."[33]

Rings and ringstones

Among the most plunderable portables from the Etruscan tombs of Etruria are the finely engraved gemstones set in patterned gold to form circular or ovoid pieces intended to go on finger rings. Of the magnitude of one centimeter, they are dated to the Etruscan floruit from the 2nd half of the 6th to the 1st centuries BC. The two main theories of manufacture are native Etruscan[34] and Greek.[35]

The materials are mainly dark red cornelian with agate and sard coming in from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC along with purely gold finger rings of a hollow engraved bezel. The engravings, mainly cameo, but sometimes intaglio, depict scarabs at first and then scenes from Greek mythology, often with heroic personages called out in Etruscan. The gold setting of the bezel bears a border design, such as cabling.

Coins

Etruscan-minted coins date ca. 500-200 BC. Use of the Euboïc-Syracusan standard, based on the silver litra of 13.5 grams maximum, indicates the custom, like the alphabet, came from Greece. Roman coinage supplanted Etruscan, but the basic Roman coin, the sesterce, is believed to have been based on the 2.5 denomination Etruscan coin.[36] Etruscan coins have turned up in caches or individually in tombs and in excavations seemingly at random, concentrated, of course, in Etruria.

Etruscan coins were in gold, silver and bronze, the gold and silver usually having been struck on one side only. The coin bore a denomination, a minting authority name, and a cameo motif. Gold denominations were in units of silver; silver, in units of bronze. Full or abbreviated names are mainly Pupluna (Populonia), Vatl or Veltuna (Vetulonia), Velathri (Volaterrae), Velzu or Velznani (Volsinii) and Cha for Chamars (Camars). Insignia are mainly heads of mythological characters or depictions of mythological beasts arranged in a symbolic motif: Apollo, Zeus, Janus, Athena, Hermes, griffin, gorgon, sphinx, hippocamp, bull, snake, eagle, etc.

Sounds

In the tables below, conventional letters used for transliterating Etruscan are accompanied by likely pronunciation in IPA symbols within the square brackets, followed by examples of the early Etruscan alphabet which would have corresponded to these sounds:

Vowels

The Etruscan vowel system consisted of four distinct vowels. Vowels "o" and "u" appear to have not been phonetically distinguished based on the nature of the writing system where only one symbol is used to cover both in loans from Greek (e.g. Greek κώθων kōthōn > Etruscan qutun "pitcher").

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i [i] |

u [u] |

|

| Mid | e [e] |

||

| Open | a [ɑ] |

Consonants

Table of consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m [m] |

n [n] |

||||||

| Plosive | p [p] |

φ [pʰ] |

t, d [t] |

θ [tʰ] |

c, k, q [k] |

χ [kʰ] |

||

| Affricate | z [ts] |

|||||||

| Fricative | f [ɸ] |

s [s] |

ś [ʃ] |

h [h] |

||||

| Approximant | l [l] |

i [j] |

v [w] |

|||||

| Rhotic | r [r] |

|||||||

Voiced stops missing

The Etruscan consonant system primarily distinguished between aspirated and non-aspirated stops. There were no voiced stops and loanwords with them were typically devoiced, e.g. Greek thriambos was borrowed by Etruscan, becoming triumpus and triumphus in Latin.[37]

Syllabic theory

Based on standard spellings by Etruscan scribes of words without vowels or with unlikely consonant clusters (e.g. cl 'of this (gen.)' and lautn 'freeman'), it is likely that /m n l r/ were sometimes syllabic sonorants. Thus cl /kl̩/ and lautn /ˈlɑwtn̩/.

Rix postulates several syllabic consonants, namely /l, r, m, n/ and palatal /lʲ, rʲ, nʲ/ as well as a labiovelar spirant /xʷ/ and some scholars such as Mauro Cristofani also view the aspirates as palatal rather than aspirated but these views are not shared by most Etruscologists. Rix supports his theories by means of variant spellings such as amφare/amφiare, larθal/larθial, aranθ/aranθiia.

Word formation

Etruscan was inflected, varying the endings of nouns, pronouns and verbs. It also had adjectives, adverbs and conjunctions, which were uninflected.

Nouns

Etruscan substantives had five cases, a singular and a plural. Not all five cases are attested for every word. Nouns merge the nominative and accusative; pronouns do not generally. Gender appears in personal names (masculine and feminine) and in pronouns (animate, or either masculine and feminine, and inanimate or neuter); otherwise, it is not marked.[38]

Unlike the Indo-European languages, Etruscan noun endings were more agglutinative, with sometimes two or three endings added instead of alternative endings; for example, where Latin would have distinct nominative plural and dative plural endings, Etruscan would suffix the case ending to a plural marker: Latin nominative singular fili-us, "son", plural fili-i, dative plural fili-is, but Etruscan clan, clen-ar and clen-ar-aśi.[39]

Pallottino calls this phenomenon "morphological redetermination", which he defines as "the typical tendency ... to redetermine the syntactical function of the form by the superposition of suffices."[40] His example is Uni-al-θi, "in the sanctuary of Juno", where -al is a genitive ending and -θi a locative. Steinbauer uses the term "inflecting language" (rather than inflected), which he explains as a language in which "... there can be more than one marker ... to design a case, and ... the same marker can occur for more than one case."[41] The etruscans would write the consonants as a base leaving the vowels back and forth. Thus creating new latin words from greek.f.ex. morphe( morfe) mrf= forma

Nominative/Accusative Case:

No distinction is made between nominative and accusative of nouns. Common nouns use the unmarked root. Names of males may end in -e: Hercle (Hercules), Achle (Achilles), Tite (Titus); of females, in -i, -a or -u: Uni (Juno), Menrva (Minerva), Zipu. Names of gods may end in -s: Fufluns, Tins; or they may be the unmarked stem ending in a vowel or consonant: Aplu (Apollo), Paχa (Bacchus), Turan.

Genitive case:

Pallottino defines two declensions based on whether the genitive ends in -s/-ś or -l.[42] In the -s group are most noun stems ending in a vowel or a consonant: fler/fler-ś, ramtha/ramtha-ś. In the second are names of females ending in i and names of males that end s, th or n: ati/ati-al, Laris/Laris-al, Arnθ/Arnθ-al. After l or r -us instead of -s appears: Vel/Vel-us. Otherwise a vowel might be placed before the ending: Arnθ-al instead of Arnθ-l.

There is a patronymic ending: -sa or -isa, "son of", but the ordinary genitive might serve that purpose. In the genitive case morphological redetermination becomes elaborate. Given two male names, Vel and Avle, Vel Avleś means "Vel son of Avle." This expression in the genitive become Vel-uś Avles-la. Pallottino's example of a three-suffix form is Arnth-al-iśa-la.

Dative case:

The dative ending is -si:Tita/Tita-si.[38]

Locative case:

The locative ending is -θi: Tarχna/Tarχna-l-θi.[43]

Pronouns

Personal pronouns refer to persons; demonstrative point out: English this, that.[44]

Personal

The first person personal pronoun has a nominative mi ("I") and an accusative mini ("me"). The second person has a dative singular une ("to thee"), an accusative singular un ("thee") and an accusative plural unu ("you"). The third person has a personal form an ("he" or "she") and an inanimate in ("it").

Demonstrative

The demonstratives are ca and ta used without distinction. The nominative/accusative singular forms are: ica, eca, ca, ita, ta; the plural: cei, tei. There is a genitive singular: cla, tla, cal and plural clal. The accusative singular: can, cen, cn, ecn, etan, tn; plural cnl. Locative singular: calti, ceiθi, clθ(i), eclθi; plural caiti, ceiθi.

Adjectives

Though uninflected, adjectives fall into a number of types formed from nouns with a suffix:

- quality, -u, -iu or -c: ais/ais-iu, "god/divine"; zamaθi/zamθi-c, "gold/golden."

- possession or reference, -na, -ne, -ni: paχa/paχa-na, "Bacchus, Bacchic"; laut/laut-ni, "family/familiar" (in the sense of servant)

- collective, -cva, -chva, -cve, -χve, -ia: sren/sren-cva: "figure/figured"; etera/etera-ia, "slave/servile"

Adverbs

Adverbs are unmarked: etnam, "again"; θui, "now"; θuni, "at first." Most Indo-European adverbs are formed from the oblique cases, which become unproductive and descend to fixed forms. Cases such as the ablative are therefore called "adverbial." If there is any such system in Etruscan it is not obvious from the relatively few surviving adverbs.

Verbs

Verbs had an indicative mood and an imperative mood. Tenses were present and past. The past tense had an Active voice and a Passive voice.

Present active

Etruscan uses a verbal root with a zero suffix or -a without distinction to number or person: ar, ar-a, "he, she, we, you, they make."

Past or preterite active

The -ce or -ke suffix to the root produces a third person singular active, which has been called variously a "past", a "preterite" or an "aorist." In contrast to Indo-European, this form is not marked for aspect, nor are the roots, apparently, distinguished for their aspect; they are simply actions that went on in the past. Examples: tur/tur-ce, "gives/gave"; sval/sval-ce, "lives/lived."

Past passive

The third person past passive is formed with -che: mena/mena-ce/mena-che, "offers/offered/was offered."

Vocabulary

- See the list of Etruscan words and list of words of Etruscan origin at Wiktionary, the free dictionary and Wikipedia's sibling project

The Etruscan vocabulary is now a few hundred words known with some certainty. The exact count depends on whether the different forms and the expressions are included. The Wiktionary list referenced above is in alphabetic order. Below is a table of some of the words grouped by topic.[45]

Some words with corresponding Latin or other Indo-European forms are likely loanwords to or from Etruscan. For example, neftś "nephew", is probably from Latin (Latin nepōs, nepōtis; German Neffe, Old Norse nefi). A few dozen from Etruscan survive in Latin; for example, elementum (letter), litterae (writing), cera (wax) (κηρός in Ancient Greek), arena (sand).

At least one word has an apparent Semitic origin: talitha "girl" (Aramaic; could have been transmitted by Phoenicians).

The Etruscan numerals are known although debate lingers about which numeral means "four" and which "six" (huθ or śa). Numerals are listed in their own article. Of them, and of the basic words in general, Bonfante (1990) says:[46] "What these numerals show, beyond any shadow of a doubt, is the non-Indo-European nature of the Etruscan language. Basic words like numbers and names of relationships are often similar in the Indo-European languages, for they derive from the same root."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bonfante (1990), page 12

- ↑ Bonfante (1990) page 10.

- ↑ For Urgulanilla, see Suetonius, Life of Claudius, Section 26.1; for the 20 books, same work, Section 42.2.

- ↑ A summary of the locations of the inscriptions published in the EDP project, given below under External links, is stated in its Guide.

- ↑ 1.30.2.

- ↑ G. M. Facchetti (2001) "Qualche osservazione sulla lingua minoica" Kadmos 40/1, p. 1-38.

- ↑ For example, Steinbauer (1999).

- ↑ Page 83.

- ↑ R.S.P. Beekes, The Origin of the Etruscans, Biblioteca Orientalis vol. 59 (2002), pp. 206–242.

- ↑ Robertson, Ed (2006) (PDF). Etruscan's genealogical linguistic relationship with Nakh-Daghestanian: a preliminary evaluation. http://www.nostratic.ru/books/(329)EGRWND.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ↑ Starostin, Sergei; Orel, Vladimir (1989). "Etruscan and North Caucasian". In Shevoroshkin, Vitaliy. Explorations in Language Macrofamilies. Bochum Publications in Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics. Bochum.

- ↑ http://www.szabir.com/blog/etruscans-huns-and-hungarians/

- ↑ http://www.szabir.com/blog/etruscans-huns-and-hungarians/

- ↑ Robert Ellis, The Armenian origin of the Etruscans, London: Parker, Son, & Bourn, 1861.

- ↑ Vahan M. Kurkjian (2006). History of Armenia. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology.

- ↑ Zacharie Mayani, The Etruscans Begin to Speak, 1961, Trans. Patrick Evans, London: Souvenir Press, 1962.

- ↑ The alphabet can also be found with alternative forms of the letters at Omniglot.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Bonfante (1990) chapter 2.

- ↑ Rooster ink-stand at Etruscan Art Virtual Museum.

- ↑ Bonfantes (2002) page 55.

- ↑ The Bonfantes (2002) page 56.

- ↑ Page 261

- ↑ The Bonfantes (2002), page 117 following.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 The Bonfantes (2002) page 58.

- ↑ Brief description and picture at The principle discoveries with Etruscan inscriptions, article published by the Borough of Santa Marinella and the Archaeological Department of Southern Etruria of the Italian government.

- ↑ Some Internet articles on the tombs in general are:

Etruscan Tombs at mysteriousetruscans.com.

Scientific Tomb-Robbing, article in Time, Monday, Feb. 25, 1957, displayed at www.time.com.

Hot from the Tomb: The Antiquities Racket, article in Time, Monday, Mar. 26, 1973, displayed at www.time.com. - ↑ 27.0 27.1 Refer to Etruscan Necropolises of Cerveteri and Tarquinia, a World Heritage site.

- ↑ Some popular Internet sites giving photographs and details of the necropoleis are: Cisra (Roman Caere / Modern Cerveteri) at mysteriousetruscans.com.

Chapter XXXIII CERVETRI.a — AGYLLA or CAERE., George Dennis at Bill Thayer's Website.

Aerial photo and map at mapsack.com. - ↑ A history of the tombs at Tarquinia and links to descriptions of the most famous ones is given at [1] on mysteriousetruscans.com.

- ↑ For pictures and a description refer to the Etruscan Mirrors article at mysteriousetruscans.com.

- ↑ For the dates, more pictures and descriptions, see the Hand Mirror with the Judgment of Paris article published online by the Allen Memorial Art Museum of Oberlin College.

- ↑ Representative examples can be found in the U.S. Epigraphy Project site of Brown University: [2], [3]

- ↑ Paggi, Maddalena. "The Praenestine Cistae" (October 2004), New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in Timeline of Art History.

- ↑ Classic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Beazley Archive.

- ↑ Ancient Coins of Etruria.

- ↑ J.H. Adams pages 163-164.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Bonfante (1990), page 20.

- ↑ Bonfante (1990) page 19.

- ↑ Page 263.

- ↑ Etruscan Grammar: Summary at Steinbauer's website.

- ↑ Page 264.

- ↑ Pallottino page 114, Bonfante (1990) page 41.

- ↑ The summary in this section is taken from the tables of the Bonfantes (2002) pages 91-94, which go into considerably more detail, citing examples.

- ↑ The words in this table come from the Glossaries of Bonfante (1990) and Pallottino. The latter also gives a grouping by topic on pages 275 following, the last chapter of the book.

- ↑ Page 22.

Bibliography

- Adams, J. N. (2003). Bilingualism and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521817714. Available for preview on Google Books.

- Bonfante, Giuliano; Bonfante, Larissa (2002). The Etruscan Language: an Introduction. Manchester: University of Manchester Press. ISBN 0-7190-5540-7. Preview available on Google Books.

- Bonfante, Larissa (1990). Etruscan. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07118-2. Preview available at Google Books.

- Cristofani, Mauro; et al. (1984). Gli Etruschi: una nuova immagine. Firenze, Giunti Martello.

- Cristofani, Mauro (1979). The Etruscans: A New Investigation (Echoes of the ancient world). Orbis Pub. ISBN 0-85613-259-4.

- Facchetti, Giulio M. (2000). L'enigma svelato della lingua etrusca. Roma: Newton & Compton. ISBN 9788882894580.

- Pallottino, Massimo (1955). The Etruscans. Penguin Books. Translated from the Italian by J. Cremona.

- Rix, Helmut (1991). Etruskische Texte. G. Narr. ISBN 3-8233-4240-1. 2 vols.

- Steinbauer, Dieter H. (1999). Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen. Scripta Mercaturae. ISBN 3-89590-080-X.

- Wallace, Rex E. (2008). Zikh Rasna: A Manual of the Etruscan Language and Inscriptions. Beech Stave Press. ISBN 978-0-9747927-4-3.

- Woudhuizen, Frederik Christiaan. April 2006. The Ethnicity of the Sea Peoples. Doctoral dissertation; Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Faculteit der Wijsbegeerte.

See also

- Combinatorial method (linguistics)

- Corpus Inscriptionum Etruscarum

- Etruscan alphabet

- Etruscan civilization

- Etruscan documents

- Liber Linteus — An Etruscan linen book that ended as mummy wraps in Egypt.

- Tabula Cortonensis — An Etruscan inscription.

- Cippus perusinus — An Etruscan inscription.

- Pyrgi Tablets — Bilingual Etruscan-Phoenician golden leaves.

- Etruscan mythology

- Etruscan numerals

- Lemnian language

- List of English words of Etruscan origin

- List of Spanish words of Etruscan origin

- Raetic language

- Robert S. P. Beekes

- Tyrsenian languages

External links

General

- Etruscan News Online, the Newsletter of the American Section of the Institute for Etruscan and Italic Studies.

- Etruscan News back issues, Center for Ancient Studies at New York University.

- Etruscology at Its Best, the website of Dr. Dieter H. Steinbauer, in English. Covers origins, vocabulary, grammar and place names.

- Viteliu: The Languages of Ancient Italy at web.archive.org.

- The Etruscan Language, the linguistlist.org site. Links to many other Etruscan language sites.

Inscriptions

- ETP: Etruscan Texts Project A searchable database of Etruscan texts.

- Etruscan Inscriptions in the Royal Ontario Museum, article by Rex Wallace displayed at the umass.edu site.

- Etruscan; The Pyrgi Bilingual, paper by Michael Weiss, Cornell University.

Lexical items

- An Etruscan Vocabulary at web.archive.org. A short, one-page glossary with numerals as well.

- Etruscan Vocabulary, a vocabulary organized by topic at etruskisch.de, in English.

- Etruscan-English Dictionary at iolairweb.co.uk. An extensive lexicon compiled from other lexicon sites. Links to the major Etruscan glossaries on the Internet are included.

Fonts

- Etruscan and Early Italic Fonts, download site by James F. Patterson at webspace.utexas.edu.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||